The Long Game 109: The Obsession with Optimization, Travel is no Cure for the Mind, Luxury Beliefs, Steroids

🛸 UFOs, Sri Lanka, Discz, Snapchat, Operating Well, Once in a Lifetime, Nuclear Power Plants, and Much More!

Hi there, it’s Mehdi Yacoubi, co-founder at Vital, and this is The Long Game Newsletter. To receive it in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

💌 We’re inviting more and more people to Vital. If you want to be part of our early community, please, fill in this form! 💪

In this episode, we explore:

The obsession with optimization

Travel is no cure for the mind

Once in a lifetime

Operating well

Luxury beliefs

UFOs

Let’s dive in!

🥑 Health

🤯 The Obsession with Optimisation

There is a recurring theme I think about all the time: obsessing over optimizing health, improving metrics, and tracking can (easily) lead to the opposite result.

I thought this week was the right time to discuss this after I read this paper Sian Allen shared: Orthosomnia: Are Some Patients Taking the Quantified Self Too Far?

Here’s the abstract:

The use of wearable sleep tracking devices is rapidly expanding and provides an opportunity to engage individuals in monitoring of their sleep patterns.

However, there are a growing number of patients who are seeking treatment for self-diagnosed sleep disturbances such as insufficient sleep duration and insomnia due to periods of light or restless sleep observed on their sleep tracker data.

The patients' inferred correlation between sleep tracker data and daytime fatigue may become a perfectionistic quest for the ideal sleep in order to optimize daytime function. To the patients, sleep tracker data often feels more consistent with their experience of sleep than validated techniques, such as polysomnography or actigraphy.

The challenge for clinicians is balancing educating patients on the validity of these devices with patients' enthusiasm for objective data. Incorporating the use of sleep trackers into cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia will be important as use of these devices is rapidly expanding among our patient population.

In short, this paper demonstrates how easy it is for some to become obsessed with the tracking and data they’re gathering continuously. It would be easy for companies in the health optimization space to dismiss this result, but I believe this is a bad idea. It is a real problem that needs to be addressed to make the most of health tracking instead of leading people to an unhealthy obsession. The solution is in the product design of those solutions.

A simple example of how to resolve those types of issues would be to assess the data only once per week, to access directly to your trends and not be obsessed with daily readings that might contain a lot of variance and inexplicable results. A similar thing could be done for people looking to lose weight, checking their weight only once per week to get the weekly trend. This is something we think about all the time at Vital.

Personally, I had a terrible experience while tracking some health parameters where I’m not in the “good” range. I found it detrimental to constantly be exposed to “bad” data and not helpful at all. Furthermore, on sleep tracking, for example, I had some of my best training sessions after an “average” recovery score (65—70 on Oura.)

🌱 Wellness

🧘♀️ Travel is No Cure for the Mind

It’s tempting to see traveling as the thing we need to “relax and feel better,” but it’s not so obvious traveling cures what people usually believe it will cure. Through a mix of mimetic desire and Instagram posts & stories, traveling became a must for a whole generation.

This post presents an interesting and different thesis around travel:

It’s just another day… and you’re just doing what you need to do.

You’re getting things done, and the day moves forward in this continuous sequence of checklists, actions, and respites.

But at various moments of your routine, you pause and take a good look at your surroundings.

The scenes of your everyday life. The blur of this all-too-familiar film.

And you can’t help but to wonder…

If there is more to it all.

For some reason — this country, this city, this neighborhood, this particular street — is the place you are living a majority of your life in.

And it is this thought that allows a daydream to seep in.

You start thinking of all the other places you could be in this world.

Or more accurately, all the places you’d rather be in.

Somewhere more exciting. Somewhere new. Somewhere that can provide experiences that are foreign to you.

You dream of going to the beautiful beaches of Thailand.

Here’s the conclusion:

While travel does expand and stretch the horizons of what we know about the world, it is not the answer we’re looking for in times of unrest. To strengthen the health of the mind, the venue to do that in is the one we are in now.

It is location-independent, and always will be.

The key is not to discard The Box of Daily Experience and find a new one — it’s to warmly embrace the one that we have now — with its joys, its flaws, and everything in between.

I agree with the core thesis of this piece. Since I deleted Instagram, my travel dreams drastically diminished (living in Barcelona might also have been a contributing factor, I must admit!)

🧠 Better Thinking

🎰 Once in a Lifetime

How come so many rare events happen all the time? Aren’t these types of events supposed to be rare?

If one person plays the lottery, the odds of picking the winning numbers twice are indeed 1 in 17 trillion.

But if one hundred million people play the lottery week after week – which is the case in America – the odds that someone will win twice are actually quite good. Diaconis and Mosteller figured it was 1 in 30.

That number didn’t make many headlines.

'‘With a large enough sample, any outrageous thing is apt to happen,” Mosteller said.

That’s part of why the world seems so crazy, and why once-in-a-lifetime events seem to happen regularly.

There are so many “rare events” that the whole category of “rare events” isn’t so rare anymore:

The idea that incredible things happen because of boring statistics is important, because it’s true for terrible things too.

Think about 100-year events. One-hundred-year floods, hurricanes, earthquakes, financial crises, frauds, pandemics, political meltdowns, economic recessions, and so on endlessly. Lots of terrible things can be called “100-year events”.

A 100-year event doesn’t mean it happens every 100 years. It means there’s about a 1% chance of it occurring on any given year. That seems low. But when there are hundreds of different independent 100-year events, what are the odds that one of them will occur in a given year?

Pretty good.

Here’s another (gloomy) example:

⚡️ Startup Stuff

🚂 Operating Well — Lessons from Stripe

Sam Gerstenzang wrote an excellent piece describing some lessons and learnings from his time at Stripe. I recommend the whole article, and I particularly liked this part:

Raise the bar.

Turn up the heat in every interaction and ask uncomfortable questions. Some of the questions I repeatedly ask:

Can we re-frame this in terms of the customer’s problem?

What’s the soonest we could get this done?

What would you need to get this done tomorrow instead of next week?

What would we need to do to get twice as many customers? Ten times as many customers?

How does this relate to our goal? Is this the most important thing we can do for our goal?

What’s most important? What do we really need to get right?

What could we cut, even if it’s painful?

Unblock psychological barriers. When something isn’t getting done, it’s because the person a) doesn’t have the time b) doesn’t have the skill or c) has some sort of psychological block. The third case is surprisingly common. After a few slips with someone I trusted, I’d just ask directly. “I noticed this work isn’t being pushed forward at the rate I expected or at the quality you normally deliver - what’s holding you back?” which would open up a conversation.

Creating psychological safety. Whenever you really push ambitions, there’s going to be some stress in the environment. That’s good. What you don’t want to happen is unsustainable stress, or for people to not share failure or tell you when you’re wrong. So you need to actively fight this as the leader by: a) asking for dissent (“does everyone agree this is the right path? Does anyone disagree”? and letting a silence hang until someone speaks) b) reward debate. If someone dissents, have the live conversation in front of others. If you still want to stay on the same path, openly discuss why you’ve made your decision and thank the person for their view. If you’re not changing your path sometimes, you’re either not listening, not creating safety, or aren’t hiring great people.

Pair with: John Collison in conversation with Stanley Druckenmiller

I particularly liked the part on work ethic. Druckenmiller explains that it was effortless for him to work hard, as he was obsessed with predicting where the markets would be in 12-18 months. Hard to beat someone that’s having fun.

The idea of “being hot” and “being cold” is also fundamental and applicable to any job. Some days, everything seems to be working, and you need to make the magic happen on those days. Some other days, nothing works, and you need to cut your losses to a minimum on those days.

📚 What I Read

☢️ Why are nuclear power construction costs so high?

Nuclear power is the best solution to climate change. Why are nuclear power plants getting so expensive?

This environment of constant change helps explain the huge increase in labor costs - changing an in-progress plant will add costs and slow down construction, even if the design changes don’t result in substantially more material or equipment use.

A universal tenet of large construction projects (and small construction projects) is that you should avoid making design changes during construction. Changes while a project is in-progress may require existing work to be removed, or new work to be done in difficult conditions. It often requires significant coordination effort just to figure out what work has been done (“Have you poured these foundations yet? Are the columns in yet?”), and what can and can’t be done in that situation. If a pipe needs to run through a beam, it’s easy to design the beam to accommodate that ahead of time. But if it’s a last-minute change, and the beam has already been fabricated, you might have to field cut a hole, or add reinforcing. Or maybe the beam can’t accommodate the hole at all, and you need to redesign the entire piping system (which will of course impact other in-progress work.) And while this expensive redesign is happening, everyone else might need to stop their work.

On a nuclear plant, which can employ up to 5,000 construction workers at a time (one source described planning the temporary construction facilities as equivalent to planning the utilities for a small city), we might expect these sorts of disruptions to be especially severe. A 1980 study of nuclear plant craft workers found that 11 hours per week were lost due to lack of material and tool availability, 8 hours a week were lost in coordination with other work crews or work area overcrowding, and 5.75 hours per week were lost redoing work. All together nearly 75% of working hours were lost or unproductively used.

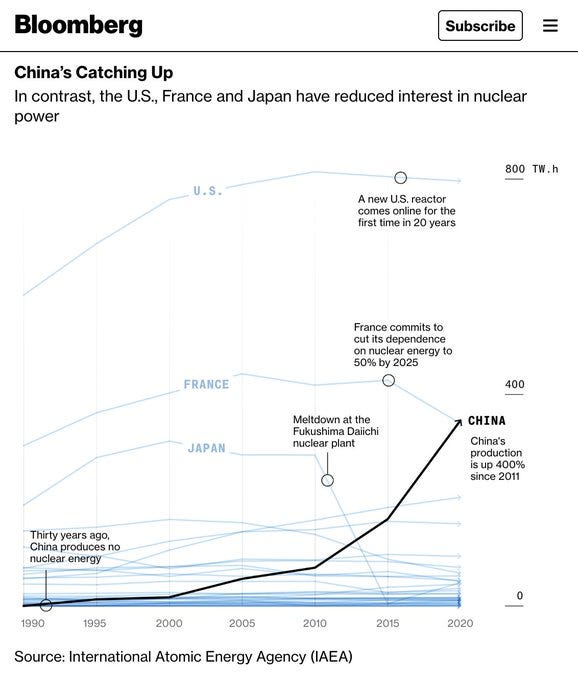

Pair with: the West is abandoning nuclear at the time it’s the most needed

⏱ Luxury Beliefs are Status Symbols

The struggle for distinction has exited the material world and entered the world of ideas:

Throughout my experiences traveling along the class ladder, I made a discovery:

Luxury beliefs have, to a large extent, replaced luxury goods.

Luxury beliefs are ideas and opinions that confer status on the upper class, while often inflicting costs on the lower classes.

In 1899, the economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen published a book called The Theory of the Leisure Class.

Drawing on observations about social class in the late nineteenth century, Veblen’s key idea is that because we can’t be certain about the financial status of other people, a good way to size up their means is to see whether they can afford expensive goods and leisurely activities.

This explains why status symbols are so difficult to obtain and costly to purchase.

📱 How to Turn Down a Billion Dollars: The Snapchat Story

I’ve recently been fascinated with Snap, their story is worth reading about, and Snap as a whole is hugely underrated (even with the recent 📉). I picked this book on the story of the company:

Evan used the analytics tool Flurry to track Picaboo’s users and their activity, gaining information on where they were located, how often they opened the app, and how long they used it for. He hoped they could hit at least 30 percent retention with Picaboo—that is, have roughly one-third of people on the app come back and use it again a week later. If they could clear this hurdle, it would show they were onto something useful with Picaboo—that they were solving a need for users and were close to product-market fit.

The guys were getting some decent feedback on Picaboo from friends who were downloading it and The guys were getting some decent feedback on Picaboo from friends who were downloading it and testing it out, but Evan knew he needed to make it more immediately appealing to his target market. Reggie’s marketing and PR efforts weren’t gaining much traction, so Evan stepped in. Picaboo needed to quickly capture people’s attention when they landed on the App Store page, drawing them in to at least read about the app, and hopefully download it. A mutual friend put him in touch with Elizabeth Turner, an aspiring model who was living in Los Angeles for the summer. Turner and her sister Sarah agreed to model for Picaboo, which Evan described as a class project, for free.

🍭 Brain Food

🛸 UFOs

I went back down the UFO rabbit hole last weekend after watching this clip with physicist Michio Kaku. It’s mind-blowing. I always find it surprising that many scientists roll their eyes when the topic of UFOs arises. They see the matter as gimmicky, based on nothing, and claim that it would be impossible for an extraterrestrial civilization to come from so far and other similar arguments.

It strikes me as extremely short-sighted, similar to how a prehistoric human would claim how impossible it is to travel from one city to another at 700 km/h.

I think this topic must be approached with an open mind, trying to gather as many clear data points as possible.

Mike Solana puts it perfectly:

It’s a sense of truth we have about the world comprised of what we’ve previously seen, experienced, and learned from people we trust. New knowledge is added to the barrier in increments, and while we change our opinions all the time, anything sufficiently distant from our core sense of the world is instinctively, and almost immediately abandoned. This isn’t necessarily because wild new information about the nature of our reality is untrue, though it often is, but because “wild” new information tends to challenge in some fundamental way our core beliefs, and reconception of core beliefs is exhausting. So, while the particular character and intensity of any given barrier belief is mostly personal, its purpose, in all of us, is universal: it exists to stop us from thinking. In my case, I once believed that people mostly understood the world. I was a total materialist in my early twenties, or so I’d convinced myself, and this was an important aspect of my identity. Fairies and spirits and raining blood were unserious topics, and so to entertain them seriously would have required submission in myself to the notion I was, in some fundamental respect, an idiot. But back at the publishing house, in that quiet closet library, I was all alone. No one was watching. What was really the harm in reading on? I arrived at Fort’s accounting of “strange lights” in the sky. Aliens, he speculated, nearly five decades before the term “UFO” was coined.

If you want to go down the 🛸 rabbit hole, I got you covered:

🎥 What I’m Watching

🇱🇰 Why Sri Lanka is Collapsing: the Coming Global Food Crisis

A grim outlook on what could be coming to the developing world:

💉 How Steroids Became More Popular Than Heroin

A lot of fitness enthusiasts aren’t aware of how prevalent steroid use is. This is a problem because it leads to unrealistic standards in mind. Typically, being huge and very lean isn’t achievable naturally.

I think people should have the agency to do what they want with their bodies, but I personally think the risk is absolutely not worth the benefits of taking steroids. It reduces fertility, brings your natural testosterone production to a halt (you’re dependent on the hormone you take), and comes with an increased risk for heart diseases and many other diseases. For more information, check out this informative channel.

Pair with: Stay Natty Bro (The steroid prevalence doesn’t mean that it’s impossible to achieve exceptional results naturally, though!)

🔧 The Tool of the Week

🎵 Discz — Discover New Music

Continuing my exploration of vertical social networks, I came across Discz. Think ‘Spotify x Tinder’ to help you discover new songs you’ll like. It’s a very well-done product.

🪐 Quote I’m Pondering

The desire to be seen as clever often prevents us from becoming so.

— La Rochefoucauld

If you enjoyed this newsletter, make sure to subscribe if you haven’t 👇

👋 EndNote

Thanks for reading!

If you like The Long Game, please share it on social media or forward this email to someone who might enjoy it. You can also “like” this newsletter by clicking the ❤️ just below.

Until next week,

Mehdi Yacoubi

PS: Lots of newsletters get stuck in Gmail’s Promotions tab. Please help train the algorithm by dragging it to Primary if you find it there. It makes a big difference.