The Long Game 170: Genomics, Embryo Selection, Expectations, Taking Yourself Seriously

AI is rewiring the economy, the hunger to be everything, some cool brands, and much more!

Hi, it’s Mehdi Yacoubi, co-founder at Mirage Metrics, OrderFlow and Mirage Exploration.

This is The Long Game, a weekly newsletter about technology, operations, AI, building a company, health, wellness and the decisions that compound over years. More than 5,000 people read it every week.

If you want it in your inbox, you can subscribe here:

In this episode, we explore:

Nucleus Genomics debacle

Expectations

Taking yourself seriously

AI is Rewiring the Economy

The hunger to be everything

Let’s dive in!

Health

What’s going on with Nucleus Genomics

A long investigative post came out about Nucleus Genomics, a startup that sells genetic testing and embryo selection services. The idea behind these services is simple: during IVF, you can choose the embryo with the lowest predicted risk of certain diseases, based on polygenic scores.

It’s a serious topic because it deals directly with future children.

The problem is that almost every part of Nucleus’s story shows signs of being unreliable.

First, the company’s marketing looks fabricated. Their website shows customer testimonials with timelines that are impossible based on when their product launched, and the photos appear to be stock images or AI-generated.

Some reviews even used faces of a different ancestry than the supposed reviewer, which matters because polygenic scores are highly sensitive to ancestry.

Then there’s the lawsuit. Nucleus is being sued by Genomic Prediction, a competitor, for allegedly stealing their trade secrets. According to the complaint, two employees left GP, deleted data, disabled security cameras, and transferred confidential documents to Nucleus. Whether all claims are true or not, it’s a major red flag.

But the biggest issue is scientific. Nucleus released a whitepaper claiming a new “AI breakthrough” for embryo selection. It turns out this whitepaper is almost a copy of a competitor’s earlier paper. Same methods, same logic, even some identical wording. And even that would be forgivable if the work were solid. Instead, the paper is full of obvious mistakes: incorrect medical codes, strange definitions of diseases, unexplained data processing steps, and what looks like training and testing on overlapping datasets, which invalidates the results.

Worse, earlier analyses by third parties had already shown that many of Nucleus’s polygenic scores didn’t work as advertised. In some cases, the performance implied by their reports was mathematically impossible based on the underlying data. They were often using polygenic scores built from only a handful of genetic variants, which cannot meaningfully predict risk for common diseases.

On top of that, their terms of service say their tests are “physician-ordered,” but then say no physician reviews the results. They also forbid New York residents from using the service, even though the company is based in New York and advertises there. This likely reflects regulatory constraints, but it also shows sloppy execution.

Why does this matter?

Because embryo selection is one of the highest-stakes products in the entire consumer health space. People are making decisions that will affect their children for life. If a company can’t produce honest marketing, reliable science, or clear legal compliance, you have to question everything else: how they handle genetic samples, how they validate their models, and how they communicate risk to parents who don’t have the tools to evaluate any of this themselves.

This is a very complicated space, and when a company promises cutting-edge genetics, the work has to stand up to scrutiny, which it clearly does not here. If you scratch the surface and find copied research, fake reviews, and basic scientific errors, the trust collapses. And without trust, nothing in this field works.

I personally think it will not end well for Nucleus Genomics and its founder, and I have had this impression for years already.

Pair with: Suddenly, Trait-Based Embryo Selection

Wellness

Expectations

Your weekly punchline:

a lot of suffering is rooted in the idea that your life should be something different than it is

It reminded me of this great piece:

The only way to counter that truth is going through life with purposely low expectations.

Don’t expect a lot of economic growth.

Don’t expect great investment returns.

Don’t expect a ton of innovation.

Don’t expect politics to improve.

Expect occasional catastrophes.

Be OK with things staying roughly the way they are right now, or worse. Because for most people the way things are right now is indistinguishable from magic relative to how things used to be.

Then any little improvements that happen to come along feel incredible. You appreciate them more. Low expectations don’t make you depressed – they do the opposite, making little gains feel amazing while bad news feels normal.

It’s not easy, because the knee-jerk way to set expectations is to anchor to what everyone else has right now. But imagine the tragedy of unbelievable progress throughout your life and enjoying none of it because you expected all of it.

Pair with: Expectations and reality

Two, understand how the expectation game is played. It’s a mental game, and it’s often a crazy and agonizing game, but it’s a game that everyone is forced to play, so you should be aware of the rules and strategies. It goes like this: You think you want progress, both for yourself and for the world. But most of the time that’s not actually what you want. You want to feel a gap between what you expected and what actually happened. And the expectation side of that equation is not only important, but often it’s more in your control than managing your circumstances.

Better Thinking

On Taking Yourself Seriously

Two lines stuck with me this week:

“In my experience of life across personal, professional, and open source, I’m amazed at how many people kind of wait for things to happen to them instead of going out and making things happen for them.” (source)

“The single greatest thing you can do for your sanity is to take life seriously. We live in a profoundly irony-poisoned society and you cut off 1/100th of what life can offer you by being a goofball. The jester may be near the king but he does not sit at the hand of the father.” (source)

Both describe the same thing in different ways.

A lot of people wait. They wait for direction, luck, or someone else’s decision. They don’t decide much on their own, and they don’t push.

They just hope something shifts. Nothing meaningful comes out of that.

The irony part is similar. If everything is a joke, you never have to risk anything. You don’t fail, but you also don’t build. You stay on the edge of your own life. You’re present, but not involved.

By pretending nothing is serious, a lot of people are actually preparing a soft landing in case it fails.

The people who move forward aren’t like this. They take their life seriously enough to choose a direction, and they take enough responsibility to actually act.

Most progress is just getting out of neutral and dropping the protective layer. That’s it.

Pair with: How to go great work

AI Updates

AI is Rewiring the Economy

This is a very good piece on how AI is reshaping the economy.

You either believe AI will displace jobs or you think its hype. I think that’s the wrong question. The right question is how does AI reshape the economy.

AI will force us to reconsider commerce, consumerism and the norms of our economy. We will enter a world where consumers buy less stuff, but with much higher conversion. Middle-income consumer populations will have less disposable income as their jobs come under pressure from AI. Meaning consumerism ceases to be the driver of economic growth.

This won’t happen overnight. We’re only just seeing the earliest signs.

This economic shift happens in three phases:

First, AI commoditizes knowledge work, destroying consumer purchasing power.

Second, human behavior shifts from consumption to goal-seeking as AI handles routine tasks.

Third, new business models emerge that profit from human flourishing rather than human spending.

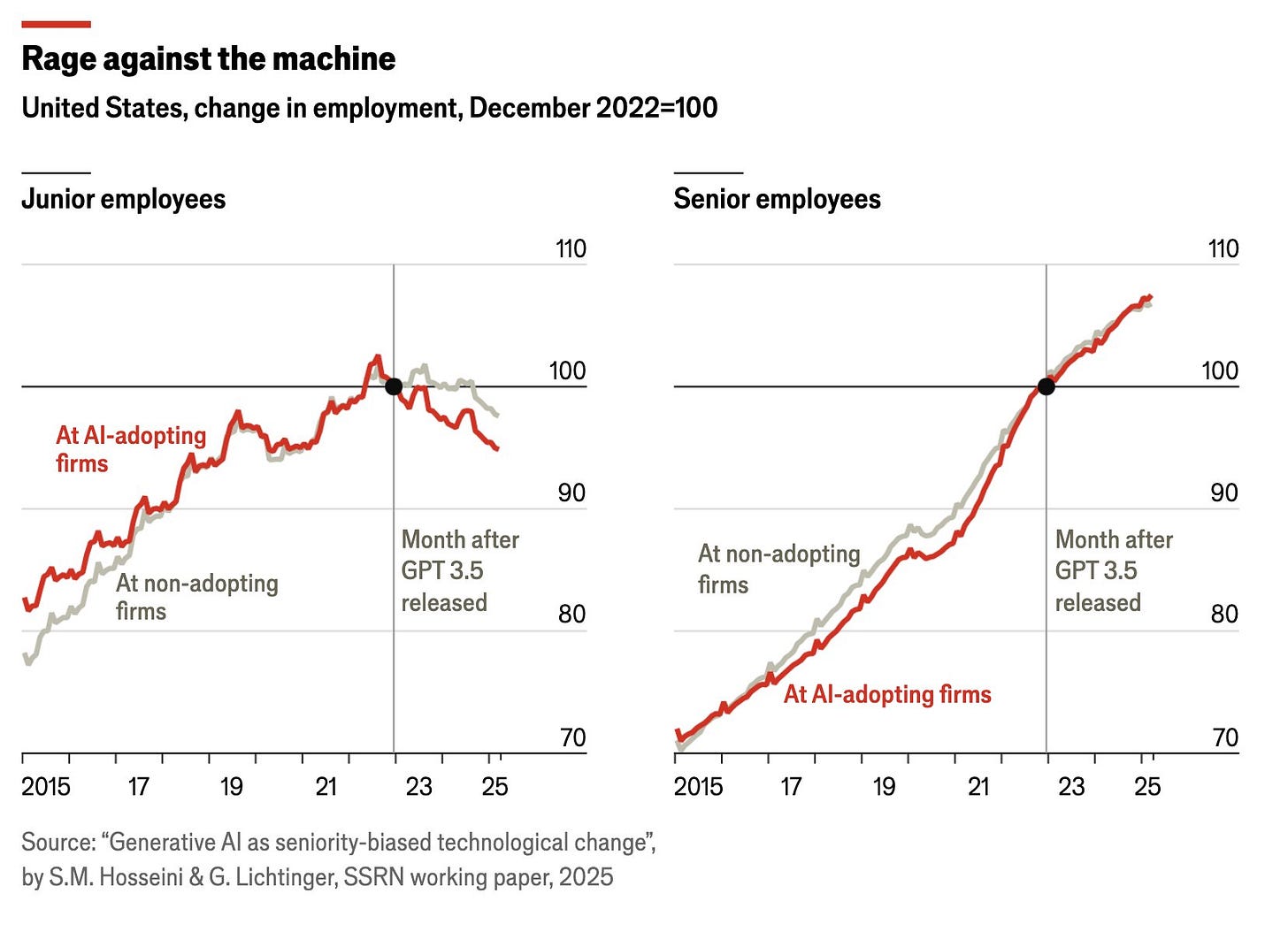

The “is it really taking jobs” is a bit of a lightening rod. But if you take at a minimum that junior level jobs are not appearing. This is worth your attention.

One line in the piece jumped out at me:

AI will reduce the cost of services like containers did to goods.

That’s the real story. Containerization made shipping almost free and rewired the entire global economy around consumerism. AI will do the same thing to knowledge work.

The author describes it clearly:

We’re about to remake the global supply chain of knowledge work.

The question then is what happens when the people who are the consumer class lose a big chunk of their income. He writes: “We created the perfect shopping platform as buying power begins to disappear.” That paradox is the interesting part. Perfect conversion, declining consumers.

Another line worth quoting: “Revenue comes from delivering outcomes, not selling stuff.” If services become cheap and abundant, the value isn’t in pushing more consumption. It’s in helping people achieve goals: health, education, money, and skills. This is where his idea of “Gross Domestic Flourishing” comes in. It isn’t idealistic. It’s an economic necessity.

If consumer spending collapses, companies either tie revenue to human outcomes or they die.

There’s a key point here: the next wave of AI companies will win by improving people’s lives in measurable ways. That’s the direction of travel, whether we like it or not. And if even part of this thesis is right, we’re heading into a world where the most valuable businesses are the ones that scale high-quality services and human capability, not consumption.

Pair with: AI will not make you rich

Let’s grant that generative AI is revolutionary (but also that, as is becoming increasingly clear, this particular tech is now already in an evolutionary stage). It will create a lot of value for the economy, and investors hope to capture some of it. When, who, and how depends on whether AI is the end of the ICT wave, or the beginning of a new one.

If AI had started a new wave, there would have been an extended period of uncertainty and experimentation. There would have been a population of early adopters experimenting with their own models. When thousands or millions of tinkerers use the tech to solve problems in entirely new ways, its uses proliferate. But because they are using models owned by the big AI companies, their ability to fully experiment is limited to what’s allowed by the incumbents, who have no desire to permit an extended challenge to the status quo.

This doesn’t mean AI can’t start the next technological revolution. It might, if experimentation becomes cheap, distributed and permissionless—like Wozniak cobbling together computers in his garage, Ford building his first internal combustion engine in his kitchen, or Trevithick building his high-pressure steam engine as soon as James Watt’s patents expired. When any would-be innovator can build and train an LLM on their laptop and put it to use in any way their imagination dictates, it might be the seed of the next big set of changes—something revolutionary rather than evolutionary. But until and unless that happens, there can be no irruption.

Also related: Companies that have adopted AI aren’t hiring fewer senior employees, but they have cut back on hiring junior ones.

Startup Stuff

Do too much

I liked re-reading this piece.

As a new founder, I’d often look at the CEOs of successful companies and wonder, “How do they do it?”

As Scale grows and as I learn on the job, I’ve come to realize that leaders of great organizations never just do it. They overdo it.

As a leader, you are the upper bound for how much anyone in your company will care. You need to do more, care more, attempt more than would seem reasonable. It will seem like overkill. But too much is the right amount.

This is true in big and small ways.

What people say is overoptimism is just optimism.

What people say is overcommunicating is just communicating.

What people say is overdelivering is just delivering.

What people say is micromanagement is just management.

What people say is ruthless prioritization is just prioritization.

It reminded me of what Duolingo’s founder said on a podcast a few years ago:

Luis von Ahn: Yeah. I mean we’ve gone through a bunch of different org charts. I mean when we were from zero to call it 30 employees, org chart was very flat, as in I was managing everybody. And that was that. And maybe I took it a little too far, but I actually think for the first zero to N where N is around maybe 20 to 30 people, the best thing you can do as a CEO is be a micromanager. I actually believe that. When you are such a small company, usually you don’t quite yet have product market fit, you haven’t really figured everything out. You have one goal, get to product market fit. And I don’t think you should be in the business of coaching people for this or that. No, no. Just I think you should micromanage people to get to product market fit. I actually believe that. At some point, it really shifts even if you love micromanaging, which I love micromanaging, but I’ve learned not to do that anymore. Even if you love it, at some point you just can’t do it as well.

Pair with: What a CEO does

“A CEO does only three things. Sets the overall vision and strategy of the company and communicates it to all stakeholders. Recruits, hires, and retains the very best talent for the company. Makes sure there is always enough cash in the bank.”

I asked, “Is that it?”

He replied that the CEO should delegate all other tasks to his or her team.

I’ve thought about that advice so often over the years. I evaluate CEOs on these three metrics all the time. I’ve learned that great CEOs can and often will do a lot more than these three things. And that is OK.

But I have also learned that if you cannot do these three things well, you will not be a great CEO.

It is almost 25 years since I got this advice. And now I am passing it on. It has served me very well over the years.

What I Read

the slow burn of becoming yourself

this is a great read. Highly recommend it.

the exhaustion of trying to belong.

Looking back, I think I understand why I felt so lost. I wanted to be like everybody else. I wanted to listen to whatever music my friends listened to. I wanted to wear whatever the pretty girls were wearing. I wanted to do cool things that can impress people. My questions weren’t “What do I truly enjoy?” but rather, “What would they want me to say?”

There’s something bone-deep exhausting about constantly shape-shifting for the sake of belonging. You become fluent in other people’s preferences, like an actor who’s learned every script but forgotten her own voice. You get good at the performance, but the performance never ends.

We mould ourselves for others because deep down, we crave love. We want to be seen, adored, chosen. It’s a deeply human instinct. But somewhere along the way, in the act of asking for love from the world, we begin carving off pieces of who we are. We offer up fragments of ourselves, hoping someone will say, “This is enough.”

And then one day, you realise: you’ve become a mosaic of other people’s expectations — but none of it feels right.

Pair with: Authenticity is a sham

the hunger to be everything.

Another great read, in a similar vein.

They told us we are lucky, to live in an era of endless doors; of infinite selves waiting to be summoned with a scroll, a post, or a step-by-step transformation.

But no one warned us of the disease it carries. Of how too much possibility can fray the edges of a person.

Our skin aches for mornings that begin with the light of dawn and not that of a screen. Before our feet touch the earth, our eyes have already wandered into someone else’s world. We didn’t notice when we stopped living and began watching others. We’ve become spectators of everyone and participants in nothing of our own.

We compare the raw underbellies of our own existence to another’s highlight reel. Our hopes now bloom from envy. Our bodies grow estranged.

And I have become a graveyard of personas. Restless in the presence of simple pleasures. Always terrified of settling. I used to think I was failing because I hadn’t arrived anywhere, but I’ve simply been lost in the contradiction of different maps, wandering too many paths.

I carry cities I’ll never walk and careers that died before a resume held their name. I mourn strangers I nearly loved; left behind in unread messages. Because what if, there’s someone else; gentler, funnier, easier, more aligned with me just one scroll further?

Pair with: Instagram is unchic and The Trouble with Optionality

For new graduates, working at a consulting firm creates optionality because of the broad exposures (to industries and companies) and skills these firms purportedly develop. Going to graduate school creates optionality by enabling more opportunities than a narrow professional trajectory can provide. Working at prestigious firms and developing social networks are similarly viewed as enabling more choices and more optionality. And of course, the more optionality, the better.

In contrast, the closing of doors and possibilities signals the loss of optionality. This language doesn’t only apply to career planning: Don’t be surprised to hear someone in finance talk about marriage as the death of optionality.

This emphasis on creating optionality can backfire in surprising ways. Instead of enabling young people to take on risks and make choices, acquiring options becomes habitual. You can never create enough option value—and the longer you spend acquiring options, the harder it is to stop.

Why the West was downzoned

Western cities used to allow dense building everywhere. Between 1890 and 1950, they mostly banned it. This “Great Downzoning” caused today’s housing shortages.

It didn’t happen because planners hated density. It happened because downzoning raised property values for suburban homeowners. Where it raised values, it passed. Where it lowered them, it failed.

Today, in big cities, strict zoning reduces property values. When owners can vote to add density, many choose to upzone.

Zoning wasn’t driven by ideals. It was driven by incentives. It will change for the same reason.

In 1890, most continental European cities allowed between five and ten storeys to be built anywhere. In the British Empire and the United States, the authorities generally imposed no height limits at all. Detailed fire safety rules had existed for centuries, but development control systems were otherwise highly permissive.

Pair with: Cities and Ambition

date someone who is interested in you

A good dating piece from the perspective of a woman. I think the dating space is completely messed up. I was lucky enough to get out of it just in time, but I’ve been studying it and reading a lot about it. I don’t think we can blame men or women as a whole; it makes no sense. However, I do believe some patterns of behavior are very unlikely to lead to something good.

This piece captures one of those patterns perfectly. She talks about giving people access to her inner world and mistaking their attention for actual understanding.

date someone who is genuinely interested in you. not just the surface-level fascination, not the curated version of you that smiles for pictures and keeps conversations light. i mean someone who slows down enough to notice what kind of silence you fall into when you’re tired, what song you hum without realizing, what time of day you seem to disappear into your thoughts. someone who pays attention not because they have to, but because knowing you feels like a privilege.

Pair with: How Dating Apps Contribute to the Demographic Crisis

Against the Odds, by James Dyson

I like to keep this book open on my laptop and read a few chapters here and there. Truly an exceptional tool to keep at hand for any founder.

On perseverance:

Life is a mountain of solvable problems, and I found that the more problems I solved, the more people told me I was wrong to try. Everyone said it couldn’t be done. Everyone said the big companies would crush us, that we didn’t understand manufacturing, that no one needed another vacuum cleaner. But the truth is simple: if you believe in an idea, you must be prepared to back it to the hilt. You must be willing to look foolish, to be wrong, to start again, and again, and again. The real failure would have been to stop.

On why being an outsider is an advantage:

What I had going for me was precisely what everyone assumed was my weakness: I knew nothing. I had no preconceptions about how a vacuum cleaner ‘ought’ to work. I wasn’t trained in the industry’s traditions, which made it easier to question them. Expertise blinds. Inexperience, combined with curiosity, lets you ask the questions experts no longer ask. Most breakthroughs begin with someone naïve enough to wonder why everyone else accepts the status quo.

On how long it really takes;

People see the finished product and call it an overnight success. They don’t see the 5,127 prototypes, the nights I thought the whole thing was collapsing, the months where I couldn’t pay myself a salary, the years when absolutely no one believed what I was building was possible. Innovation looks glamorous only in retrospect. At the time, it is a long stretch of disappointment punctuated by the rare and precious moment when something finally works.

Brain Food

Mediterranean people vs Northern People

This is a topic that keeps coming back: why some cultures seem more laid back than others. I found this answer original and probably correct (spoiler alert: it’s not the weather.)

Mediterranean people, generally speaking, just want to have fun.

It’s a Northern European phenomenon… directly attributed to Protestantism.. that prioritized work, structure, and committee governance over leisure. That mentality then transferred itself to the North American colonies and became deeply embedded in the American psyche.

This cultural package ultimately led to differences in institutions, education systems, trust in impersonal cooperation, and the timing and depth of industrialization. This is one of the important reasons the US became the global economic hegemon and why Northern European countries, in aggregate, are more productive than the southern ones. It has little to do with intelligence or sophistication and much more to do with cultural orientation toward work versus living.

You see this clearly in parenting.

In places like Greece, Spain, and southern Italy, you’ll often see adults out at 10 or 11pm on the plaza or at a restaurant, genuinely enjoying themselves while their kids run around playing in the background… and toddlers literally passed out on a bench, a chair, or in a stroller nearby.

Meanwhile, Americans and many Northern and Western Europeans put their children to bed promptly within a defined bedtime window, because the next day is structured, scheduled, and built around order, routine, and getting up on time.

One culture allows the present moment to stretch. The other organizes the present around the needs of tomorrow.

It’s all about “what’s next?” versus “experience now.”

That distinction explains a significant part… more than many people care to acknowledge… of the differences in productivity, power, and modern life in the West.

Pair with: Mediterráneo moral.

What I’m Watching

Barcelona’s Map, Explained

Pair with: 5 Big Things That Cities Could Learn from Barcelona

Pay the Price

Pair with: Discomfort is the price you pay for a fulfilling life

The Tool of the Week

Some brands I like

This, this, this, this and this. If you need ideas for the end-of-year season!

Quote I’m Pondering

No valid plans for the future can be made by those who have no capacity for living now

— Alan Watts

EndNote

Thanks for reading,

If you like The Long Game, please share it or forward this email to someone who might enjoy it!

You can also “like” this newsletter by clicking the ❤️ just below, which helps me get visibility on Substack.

Also, let me know what you think by leaving a comment!

Until next time,