The Long Game 97: Going to the Doctor, Longtermism, Art, Debunking Cynicism

🚂 Remove Barriers to Productivity, Meritocracy, Survival of the Prettiest, Amie, Your Red, and Much More!

Hi there, it’s Mehdi Yacoubi, co-founder at Vital, and this is The Long Game Newsletter. To receive it in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

In this episode, we explore:

Why going to the doctor sucks

Art should be a habit, not a luxury

Longtermism

Learning to grind when it’s boring

Removing barriers to productivity

Meritocracy

Let’s dive in!

🥑 Health

🏥 Why Going to the Doctor Sucks

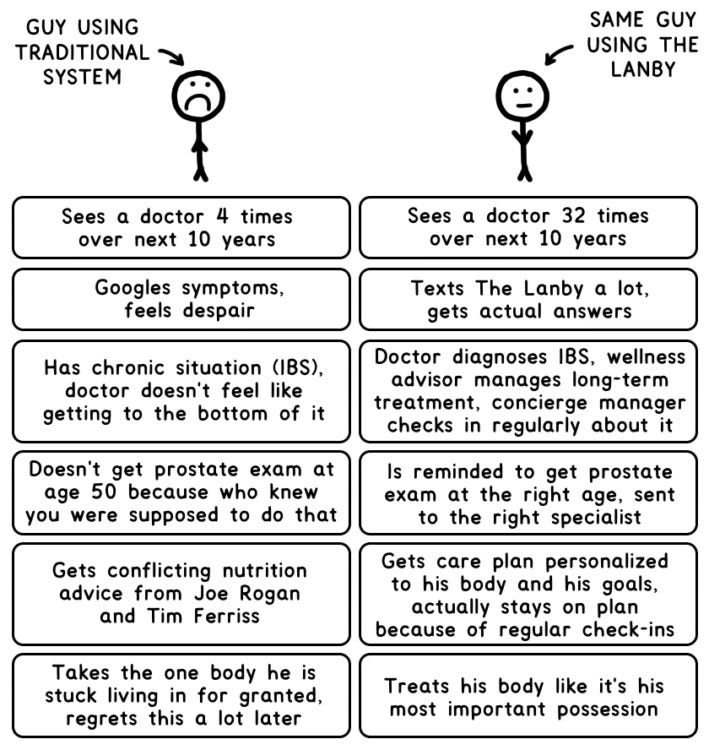

I liked this article explaining a feeling most of us share: going to the doctor sucks. Healthcare systems vary from country to country, and some do better than others, but it’s fair to say there aren’t any real health optimization systems happening on a wide scale anywhere on earth yet.

The American healthcare system is full of problems. But our health also suffers from a human nature problem.

Humans tend to be highly irrational about long-term planning, no matter how important it is. Prioritizing our health seems frivolous when we’re healthy.

This kind of thinking makes The Lanby seem like a luxury service—because $3,000/year is luxurious when spent on something frivolous. But healthcare when you’re healthy is anything but frivolous. It’s critical preventive care—the kind that prolongs (and often saves) our lives and drastically increases our chance of a happy future (and which ends up saving us money over the long run).

If humans were perfectly rational creatures, we’d all be highly attentive to our health and put the proper effort toward preventive care. But since we’re not, one fix is to hack the human system by sweetening the experience enough that our dumb short-term brains actually like going to the doctor.

If going to the doctor is an easy, lovely experience, we’ll go more often. When there’s an expert who always wants to talk to you about your diet, sleep, and exercise, we’ll live a healthier lifestyle. When it’s incredibly easy to send a text to ask a quick health question, we’ll ask more health questions. When preventive care is a way of life, we’ll have a healthier future.

It’s a problem I think about all the time because a big belief I hold is that over the next 20 years, a whole new system will be invented encompassing healthcare and health optimization to enable humans to maximize their healthspan.

Early-stage health optimization companies have a huge opportunity to build this and catalyze this revolution. This is how we envision the future at Vital.

🌱 Wellness

👨🎨 Art Should Be a Habit, Not a Luxury

I loved this article calling for more art in our lives:

Too often, we let the humdrum reality of life get in the way of the arts, which can feel frivolous by comparison. But this is a mistake. The arts are the opposite of a diversion from reality; they might just be the most realistic glimpse we ever get into the nature and meaning of life. And if you make time for consuming and producing art—the same way you make time for work and exercise and family commitments—you’ll find your life getting fuller and happier.

A good way to stop our daily obsessions with small and insignificant tasks is to experience or create art:

Engaging with art after worrying over the minutiae of your routine is like looking at the horizon after you’ve spent too long staring intently at a particular object: Your perception of the outside world expands. This refocusing enables what the Stanford neuroscientist Andrew Huberman calls panoramic vision, widening our perspective of true reality by allowing us to see more. In addition to increasing awareness of the broader world, Huberman shows that narrow vision heightens our fear response, but widening our perspective lowers stress.

Art opens our mental aperture and provides relief from the narrow tedium of will. “The true work of art leads us … [to] that which exists perpetually and time and time again in innumerable manifestations,” Schopenhauer wrote in 1851.

Finally, we might all benefit from considering art more like sleep or exercise, rather than something not essential:

If you are among the 73 percent of Americans who feel that art is “pure pleasure to experience and participate in,” you might see it the same way you see eating out, or skydiving: as a luxury item in your limited budgets of time and money. As such, it probably gets the same sort of treatment as any minor hobby.

Don’t make this error. Treat art less like a diversionary pleasure and more like exercise or sleep or loving relationships: a necessity for a life full of deep satisfaction. I’m not saying you need to quit your job and become a poet. But you should make a daily effort to get off the wheel of Ixion.

🧠 Better Thinking

♾ Longtermism

One of the biggest problems of our generations is that our wisdom hasn’t evolved as fast as our ability to destroy ourselves. It’s very dangerous because if we aren’t cautious, we could endanger all of the potential future of humankind.

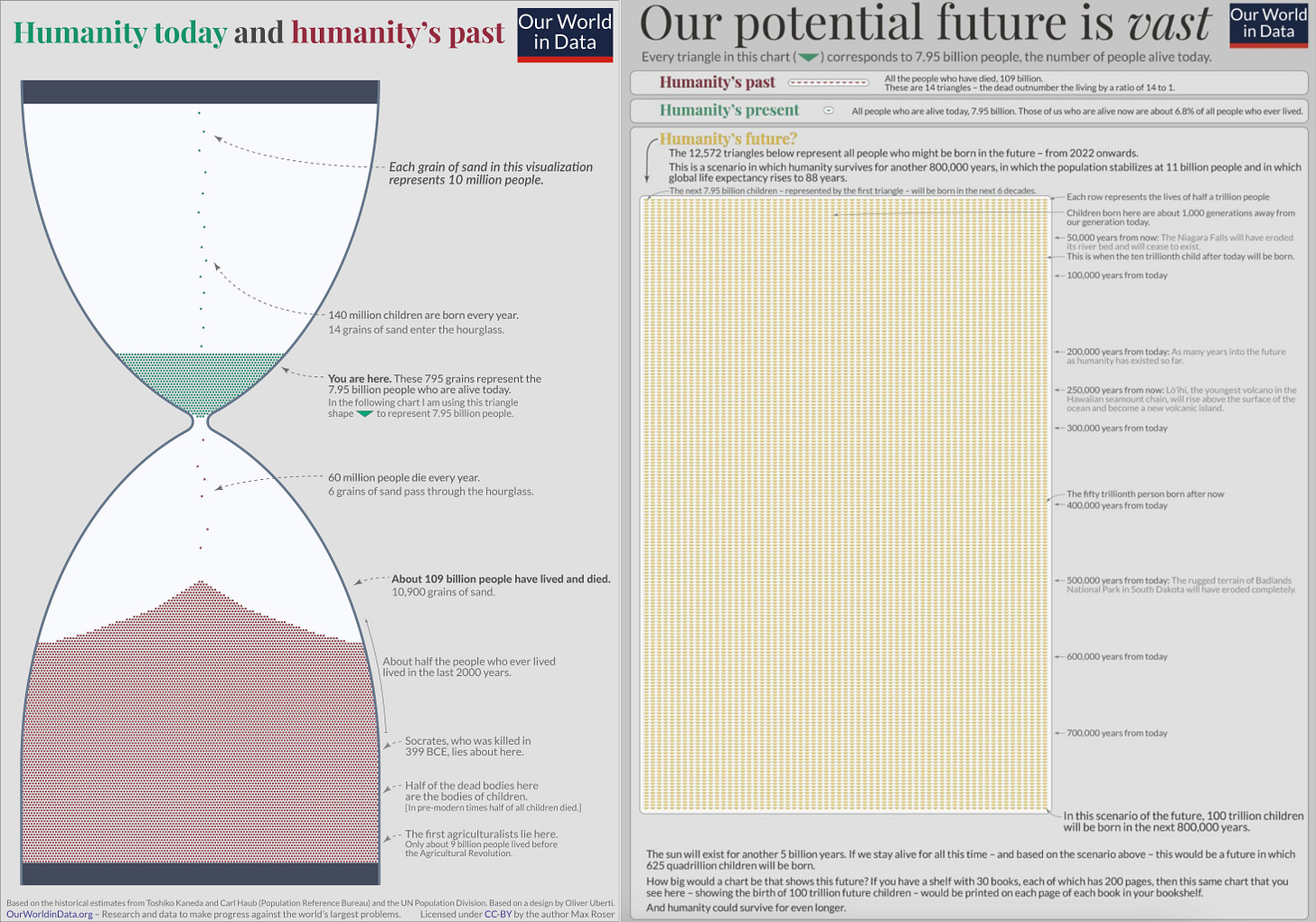

Max Roser at Our World in Data explains it perfectly.

How many people will be born in the future?

We don’t know.

But we know one thing: The future is immense, the universe will exist for trillions of years.

We can use this fact to get a sense of how many descendants we might have in that vast future ahead.

The number of future people depends on the size of the population at any point in time and how long each of them will live. But the most important factor will be how long humanity will exist.

Before we look at a range of very different potential futures, let’s start with a simple baseline.

We are mammals. One way to think about how long we might survive is to ask how long other mammals survive. It turns out that the lifespan of a typical mammalian species is about 1 million years. Let’s think about a future in which humanity exists for 1 million years: 200,000 years are already behind us, so there would be 800,000 years still ahead.

Let’s consider a scenario in which the population stabilizes at 11 billion people (based on the UN projections for the end of this century) and in which the average life length rises to 88 years.

In such a future, there would be 100 trillion people alive over the next 800,000 years.

This means that our responsibility is vast, and we should do way more to reduce existential risks:

A catastrophe that ends human history would destroy the vast future that humanity would otherwise have.

And it would be horrific for those who will be alive at that time.

The people who live then will be just as real as you or me. They will exist, they just don’t exist yet. They will feel the sun on their skin and they will enjoy a swim in the sea. They will have the same hopes, they will feel the same pain.

‘Longtermism’ is the idea that people who live in the future matter morally just as much as those of us who are alive today. When we ask ourselves what we should do to make the world a better place, a longtermist does not only consider what we can do to help those around us right now, but also what we can do for those who come after us. The main point of this text – that humanity’s potential future is vast – matters greatly to longtermists. The key moral question of longtermism is ‘what can we do to improve the world’s long-term prospects?’.

In some ways many of us are already longtermists. The responsibility we have for future generations is why so many work to reduce the risks from climate change and environmental destruction.

But in other ways we pay only little attention to future risks. In the same way that we work to reduce the risks from climate change, we should pay attention to a wider range of potentially even larger risks and reduce them.

I am definitely frightened of these catastrophic and existential risks. In addition to nuclear weapons, there are two other major risks that worry me greatly: Pandemics, especially from engineered pathogens, and artificial intelligence technology. These technologies could lead to large catastrophes, either by someone using them as weapons or even unintentionally as the consequence of accidents.

⚡️ Startup Stuff

🔁 Learning to Grind When it’s Boring

For this week, a simple yet essential insight that I learned over my first year of building something: you need to learn to grind when it’s boring when it’s not going as planned, when it’s not moving as fast as expected, etc.

It doesn’t feel good, but no one claims that building something outstanding will always feel good and be easy.

📚 What I Read

🚂 Remove Barriers to Productivity

It’s time to build:

If we can’t counterbalance the supply shock in every granular manifestation, we can at least take action to boost productivity and aggregate supply. Macroeconomic textbooks don’t focus on this policy lever because they assume that the supply side of the economy is already optimized. Yet it is manifestly evident that American society is not maximizing its productivity. If we wanted to raise American productivity, for example, we could simplify geothermal permitting, deregulate advanced meltdown-proof nuclear reactors, make it easier to build transmission lines, figure out why high-speed rail is so expensive, fix permitting generally, abolish the Jones Act, automate our ports, allow drones to operate autonomously, legalize supersonic flight over land, reduce occupational-licensing requirements, train more medical workers, build more hospitals, revamp our pandemic-response institutions, simplify drug approvals, deregulate land use to allow denser housing and mixed-use neighborhoods, allow more immigration, cancel inefficient programs, restrict cost-plus procurement contracts in favor of more effective methods, end appropriations based on job creation, avoid political direction of scientific research, and instill urgency in grantmaking.

In other words, there is much we could do to boost supply. No, not all these actions will offer relief from the specific supply shocks we could soon face; nor will they all have an immediate effect. Still, doing as much as possible now to remove barriers to productivity and efficiency is our best hope to avoid prolonged stagflation.

🧗♂️ On Meritocracy

A good discussion on meritocracy:

The term meritocracy isn’t very popular these days.

Firstly, it’s a myth. But to the extent meritocracy exists, it’s bad. A belief in meritocracy is not only false: it’s bad for you. Meritocracy makes everyone miserable. Meritocracy harms everyone — even the winners. These are all article headlines in the last few years written by people at elite publications and universities.

Meritocracy attracts universal skepticism. The left thinks meritocracy is a disguise for plutocracy — a justification of inequalities whose origins lie not in ability, but in power and privilege. The right says meritocracy is an excuse for the smug, credentialed, overclass to look down on everybody else. Others say meritocracy has fueled an individualist culture that has given up on notions of the common good.

In this piece, we’ll outline some of the critiques to meritocracy and issue some responses.

🏛 Against the Survival of the Prettiest

Many modern buildings put up today seem uglier than traditional ones around them. Some say this is because we’ve torn down the ugly old buildings and only see the survivors. Are they right?

This is an elegant theory, and in my experience it attracts a lot of clever people. It also has the obvious advantage of removing the pressure to believe that we mysteriously got worse at making attractive buildings, at the same time as we were getting better at doing so many other things. Given what a strange and counterintuitive idea this is, this is no small virtue.

I think the survivorship theory probably does accurately model some real patterns, as I will go on to explain. But I do not believe that it can be the main explanation for the scarcity of old ugly buildings. In fact, I think we have a huge amount of easily accessible evidence for this, which is sufficient to disprove the theory fairly decisively.

🎙 Podcast Episodes of the Week

This week in podcasts:

Running, overcoming challenges, and finding success | Ryan Hall

Ryan Hall is the fastest American ever to run the marathon (2:04:58) and half marathon (59:43) and is the author of the book Run the Mile You’re In.

In this episode, Ryan discusses his amazing successes and epic failures during his remarkable running career and what he’s learned through these experiences.

Ryan explains the physical aspects of running – including his training routine, fueling regimen, and recovery process – and he also emphasizes the mental aspect of the sport. He discusses how accepting and reframing negative thoughts can empower you to take on challenges and reach your potential.

Using Salt to Optimize Mental & Physical Performance

Conscious and unconscious salt intake and sensing modulates cravings for sugar, water, and other things

Sodium is the way your neurons communicate – having enough salt in the body allows the brain and nervous system to function

Sodium and water work together in the body: thirst is not just a way to bring fluid into our body – it’s an internal signal telling us to balance salt level

“If you’re craving salt, you probably need it.” – Dr. Andrew Huberman

It’s helpful to have a formula and not just consume salt and water based on craving because your body tends to adapt to certain levels of salt over time, so it doesn’t provide a consistent indicator

The notion that a high salt diet is bad for you is confounded by the fact that high salt diets are usually rich in processed foods and a poor balance of carbohydrates to fat

There’s a direct relationship between the stress system (glucocorticoid system) and the salt craving system

If you’re feeling anxious, slightly increasing sodium intake can stabilize blood pressure and ability to lean into stressors and challenges

Galpin equation for fluid replenishment during exercise or cognitively demanding activity: start exercise hydrated with electrolytes (not just water), then every 15 minutes, consume (in ounces) your body weight (in pounds) / 30

Rule of thumb if you fast or follow time-restricted eating: caffeine is a diuretic, so for every ounce of caffeine, drink 1.5x as much water with a touch of sodium

Very generalized recommended mineral intake, barring health conditions: 3.2-4.8g of sodium, 4g of potassium

You must know your blood pressure to make informed decisions about salt and fluid intake – salt needs will vary accordingly

🍭 Brain Food

🧠 The Cynical Genius Illusion

It’s sometimes believed that cynical people are somehow more intelligent than the average and know things that others (optimistic people) don’t know.

This is a great paper to debunk this common belief: “To conclude, the idea of cynical individuals being more competent, intelligent, and experienced than less cynical ones appears to be quite common and widespread, yet, as demonstrated by our estimates of the true empirical associations between cynicism and competence, largely illusory.”

Abstract:

Cynicism refers to a negative appraisal of human nature—a belief that self-interest is the ultimate motive guiding human behavior. We explored laypersons’ beliefs about cynicism and competence and to what extent these beliefs correspond to reality.

Four studies showed that laypeople tend to believe in cynical individuals’ cognitive superiority. A further three studies based on the data of about 200,000 individuals from 30 countries debunked these lay beliefs as illusionary by revealing that cynical (vs. less cynical) individuals generally do worse on cognitive ability and academic competency tasks.

Cross-cultural analyses showed that competent individuals held contingent attitudes and endorsed cynicism only if it was warranted in a given sociocultural environment.

Less competent individuals embraced cynicism unconditionally, suggesting that—at low levels of competence—holding a cynical worldview might represent an adaptive default strategy to avoid the potential costs of falling prey to others’ cunning.

🎥 What I’m Watching

🔴 Is Your Red The Same as My Red?

I had this question in my mind for as long as I can remember. This was a great attempt at answering it.

🚫 You Don’t Need to Follow That Instagram Model!

I’ve said it many times; I think Instagram has a detrimental effect on most people. I left the platform a few months ago and feel great about it. This is a great video explaining a part of the problem in the fitness/wellness niche.

🔧 The Tool of the Week

📅 Amie — The Joyful Productivity App

I haven’t used Amie yet, and I’m not even really into productivity apps anymore (I think most of them end up solving no problem at all and can easily get overhyped). Still, I must give credit when a product seems to be extremely well designed a thought.

I’ll be waiting to try Amie!

🪐 Quote I’m Pondering

“Don't fear failure. Not failure, but low aim, is the crime. In great attempts it is glorious even to fail.”

— Bruce Lee

If you enjoyed this newsletter, make sure to subscribe if you haven’t 👇

👋 EndNote

Thanks for reading!

If you like The Long Game, please share it on social media or forward this email to someone who might enjoy it. Podcast reviews are also gratefully received. You can also “like” this newsletter by clicking the heart just below this, which helps me get visibility on Substack.

Feel free to email me or find me on Twitter if you have any feedback or questions.

Until next week,

Mehdi Yacoubi

PS: Lots of newsletters get stuck in Gmail’s Promotions tab. If you find it in there, please help train the algorithm by dragging it to Primary. It makes a big difference.